About Wajima Nuri Lacquerware

Wajima Nuri is lacquerware produced in Wajima on the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. It is one of only two lacquerware production areas in Japan to be recognized as an important cultural asset by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

The History of Wajima-nuri

There are a number of theories as to how urushi production started in Wajima but as yet none of them have been confirmed. Vessels that contain locally found powder diatomaceous earth mixed in with the urushi undercoating have been discovered in a number of local excavations which date back to medieval times. From evidence found in the small number of handed down texts that have survived the centuries, it is thought that urushi lacquerware was being produced in Wajima in the Muromachi Period (1333-1573).

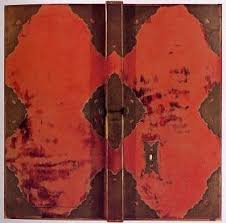

Juzo shrine doors in Wajima, the oldest Wajima nuri in existence

Important factors in the development of lacquerware production are both the local abundance of readily available materials such as Noto cypress, zelkova, urushi trees and Wajima jinoko powder diatomaceous earth ( fossilized earth ) and the area’s favorable climatic conditions. Wajima was historically a port of call on a major sea route which made it convenient for the transportation of materials and goods. This was probably an important contributing factor to the local development of the industry. However, the fact that the people involved in the production and distribution of lacquerware had such pride in their work, and that the level of the techniques were continuously being honed, are probably the most important factors in ensuring that the tradition has been passed down so successfully to the present day.

Another important factor in ensuring that Wajima-nuri became so well-known throughout Japan was a unique sales strategy which ensured that channels of distribution were constantly being developed and increased.

The Production Process of Wajima-nuri

There is a systematic division of labor in the production process of Wajima-nuri that at its broadest level can be divided into the stages of substrate production, lacquering and decoration. Within these general categories there is a further level of specialization which includes the wooden substrate crafts of wan-kiji (wood turning to produce objects composed of concentric circles), magemono (the bending of previously soaked wood to produce substrates), sashimono (the assembly of processed wood into boxes and shelves), ho-kiji (specialist carving of more complex shapes), and the lacquering techniques of shitaji (undercoating), uwa-nuri (top coating), ro-iro (polishing), maki-e (predominantly decoration through the sprinkling of gold or silver into intricate patterns) and chinkin (decoration through carving of patterns onto the surface and filling the grooves with gold and silver).

With a production process based on a system of division of labor, a piece will typically go through over one hundred stages which can take anything from six months to several years to complete. Each of the specialist fields have developed their own traditions of high level craftsmanship and efficiency at each stage of the production process which have been carefully passed down through generations and are still held in high regard today.

Each craftsman works with confidence and dedication to produce his work. The nushi-ya is the master craftsman and it is his job to manage and oversee the entire production process. From the time that an order is placed until the delivery of the product he is uncompromising in ensuring that at each stage the highest standards of quality are maintained.

Wooden Substrates

The shape of the wooden substrate differs according to its purpose and the industry is divided into trades in which craftsmen who have mastered each specialist technique work. Certain woods are more suited to certain shapes and the correct choice of wood for each shape is another important part of the production process. Whichever kind of wood is chosen, it needs to be dried for three to five years after the tree has been felled before it can be used.

Wan-Kiji

Wan-kiji, which is also known as hikimono-kiji is the technique of turning wood on a lathe a while carving it with a turning tool. It is used for producing circular vessels such as bowls, dishes, plates and pots. The woods most often used are zelkova, cherry and horse chestnut.

Sashimono-Kiji

Sashimono or kakumono, is the assembly of wood that has been made into boards. The woods most often used are Noto cypress, Japanese cypress, paulownia and gingko. The boards are used to make such things as stacked box sets, ink-stone boxes, miniature dining tables and trays.

Magemono-Kiji

Using thin prepared wood with a vertical grain, the wood is soaked in water to make it pliable and then bent into round shapes such as circular trays and lunch boxes. Good quality wood is necessary such as Noto cypress or Japanese cypress.

Ho-Kiji

Ho-kiji is also known as kurimono and falls within the field of sashimono. It is the specialist field of the production of substrates which have many curves and require the carving of more complex shapes such as tatami floor chairs, the legs of flower vases, the lips of sake vessels and spoons. The woods most often used are magnolia, katsura and Noto cypress.

Lacquering

Wajima-nuri has a characteristic lacquering method. It is known as honkataji and is a traditional technique of undercoating. Wajima has remained steadfast in keeping to this method and through continuing research has strived to achieve the highest quality possible in lacquerware. It has become the standard in Wajima lacquering. With honkataji the parts of a wooden substrate that are most prone to damage are reinforced with cloth that is applied to the wood with a mix of rice glue and urushi. Subsequent urushi undercoats are mixed with Wajima jinoko which literally means earth powder. Jinoko is high quality baked diatomaceous earth (a light soft chalk-like sedimentary rock that contains fossilized algae that give it an absorbent quality). Jinoko is extremely heat resistant and when mixed with urushi dries to form a hard and durable coating. Jinoko in Wajima is graded according to the size of the particles and is applied to the substrate mixed with urushi from the roughest ippenji (first grade) followed by successively finer grades of nihenji (second grade), sanbenji (third grade) and sometimes even yonhenji which is the fourth and finest grade. Between each stage when the surface has dried, it is sanded when dry and with each layer the finish becomes both finer and smoother.

Making the tool to apply the undercoats

Applying pure coats of urushi

Diatomaceous earth which is baked and ground

Urushi brushes with Asian women’s hair (far right with beaten tree bark)

A mixture of diatomaceous earth, urushi and rice glue used for the undercoats

The repeated undercoating process however is not just for the purpose of ensuring durability. Through careful manipulation of the thickness of coats and the sanding process between these coats of the undercoating process (also known as jitsuke), the craftsman also determines the final shape and character of the substrate. It is an extremely important stage of the production process and there is no room for error as any oversight will be visible in the finished product. In order to produce such high quality work, a considerable level of technique is required from the craftsmen to consistently maintain these standards.

In uwa-nuri, high quality refined urushi is applied to the substrate with a brush made from Asian women’s hair. Dust is the greatest enemy at this stage which requires great care and concentration not to allow it to settle on the wet urushi finish.

There are several varieties of urushi which are each used according to their individual properties. The season and climate contribute to the condition of the urushi when it is used and so it has to be carefully prepared. The experience and techniques of the uwa-nuri craftsman provide him with the ability to carefully mix and adjust the urushi so that each time it is used, an optimum coating is achieved.